ASK JUDE: “Jude – why do you always say the British Isles?”

C.W.: Contains references to UK Politics, Brexit, and one

reference to murder.

Less Serious C.W: Contains references to

Eurovision.

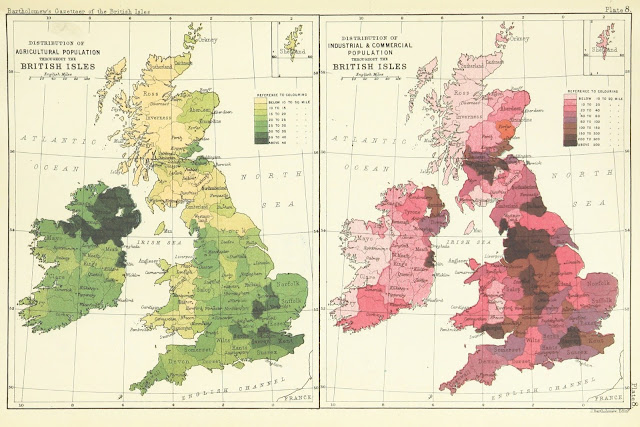

I have been asked this question a few times by fellow researchers,

and by other students, so I thought I would write a short explanation of why I

am particularly given to multiple descriptions of th is type and why when I am

setting out the geographic boundaries of a study I try to avoid using the names

of specific countries – instead referring to the physical geography of the area.

|

| British Library digitised image from page 947 of "Gazetteer of the British Isles, statistical and topographical. Edited by J. Bartholomew. With appendices and special maps and plans" |

When the Eurovision Song Contest introduced telephone

voting, a number of people – many in a unique subset who were both fans of

Eurovision and of statistics – noted that while some traditional back and forth

awarding of points continued, there were certain shifts within countries voting

patterns. Was it to do with

international relations – as Eurovision is often comedically described as being

focused on? Unlikely. In several of these first events in

televoting two particular tendencies stood out.

Great Britain awarding points to Ireland, and Germany (and later Great

Britain) awarding points to Poland. And

the most logical explanation?

Demographic change. In the early

2010s Britain experienced a wave of migration from Poland. Economic migrants taking advantage of gaps in

the UK jobs market and the relative strength of currency. Many came to work in construction, and with

them came additional businesses catering to the needs of Polish

communities. In one example, in

Eastbourne, in East Sussex, a large number of Polish migrants moved in to one

particularly run down street, and several businesses moved into previously

boarded up shops setting up Polish grocery shops, and cafes with bilingual

menus, specialising the Polish and Eastern European food. These communities were met with a mix of

racism, and respect. The work ethic of

some Polish builders was well known enough to be a punchline the BBC Radio 4

satirical programme The Now Show.

This demographic shift – the increase in a migrant population who were

both happy to be living somewhere where they could work and earn enough money

to support both themselves and their families back home – was reflected in

minor ways in things like Eurovision.

Now, the shift is partly being reversed, as Polish and other EU migrants

seek to return to their former homes particularly since the referendum on the

UK’s membership of the EU, both due to the outcome which saw Britain leave, and

the storm of xenophobia and scare tactics which, in the words of comedian Adam

Hills ‘lowered the tone of political debate {…} to somewhere between Donald

Trump and Mein Kampf’ [the full 'rant', directed at former UKIP and current Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage, which contains this line and strong language / adult humour from the start can be found here (NSFW) ] and which resulted in the murder of Labour Party MP Jo Cox. However that shift, during that

period, changed the demographics of Britain and in some ways the identity in

Britain.

The concept of countries having fixed borders is not as

old as you might think. The doctrine

that national borders were something which was agreed and that the violation of

them is unacceptable is often referred

to as ‘Westphalian sovereignty’ – which arose out of the Peace of Westphalia

(1648) – at the end of the Thirty Years War.

This set out basic principle of non-intervention in the internal affairs

of other states – and almost formalised borders. A simple explanation of the concept, and it’s

impact on the complexity of European borders by Tom Scott can be found here. The idea of nations and geography

being tied together, rather than nations to rulers is one which it could be

argued emerges in the Middle Ages as kingdoms become geographical entities to

an extent distinct from their governance.

|

| Gerard ter Borch - The Peace of Westphalia at Muenster - The ratification of the Treaty of Münster, part of the Peace of Westphalia that ended the Thirty Years' War. |

During the later part of what we might call the Early

Middle Ages and the early part of the High Middle Ages a notable transition

took place in the way in which national leaders described themselves. In the earlier part of the 10th

Century Cnut describes himself in royal proclamations as King of the English –

and later King of the English, King of the Dane. Note here the emphasis – Cnut describes

himself as the king of the people rather than the geographic territory. Historians would later label the territories

ruled by Cnut as the North Sea Empire.

|

| The North Sea Empire. Red denotes where Cnut was king, orange areas were vassal states, and yellow were nations allied to Cnut through various treaties. |

Rulership in some cases expanded by the addition of peoples rather than

geographical territory. This is not to

say that geographical territory was less significant or lacked a significant

identity – Northumbria held to an Anglo-Scandinavian identity even after it was

subjugated by the alliance of southern kingdoms centred on Wessex. When the Anglo-Saxon and other Germanic

tribes arrive to settle in territories that would become England, Gildas, in

terms perhaps not so different to those of a particularly xenophobic columnist

for the Daily Mail, writes of the Ruin of Britain.. The very name of Wales and the Welsh people

spring from the Anglo-Saxon/Old English word ‘Wēalas’ for which had a

more general meaning of foreigner – and was used by the Anglo-Saxons for

any people associated with the Brythonic tribes. When Harold Godwinson, and a large part of

the house of Godwin, fall near Hastings in 1066, it takes William I several

years to subjugate the remaining country before turning first to some efforts

in the reform of the church in 1070, and then to the conquest and subjugation

of Wales and Ireland. Even the name

Great Britain could be argued to be adapted from a terminology from outside the

islands themselves – Britannia Superior – which was the name of one of the

Roman provinces in Britain. The island

of Ireland was known in Latin as Hibernia – which was a loanword from Greek –

the later names both Ireland and Gaelic Eire come from Ériu, a

goddess in Irish mythology first recorded in the 9th century. The Norman nobility thought of themselves as

just that – Norman – speaking the Norman language – one of angues d'oïl, as

distinct from the d’oc languages of the southern region near the modern border

with Spain. Indeed this linguistic

distinction gives us the name Languedoc – geographically more or less equating

the Roman province of Gallia Narbonensis, the area was a Visigothic kingdom in

the 5th to the 8th centuries, before being briefly part

of the Emirate of Corduba in the 750s, before it was conquered by the Franks in

759. The area, which Occitan was spoken

became known as Languedoc because of the use of Occitan. Both are defined by their particular word for

‘yes’ – ‘oil’ or ‘oc’. Thus a literal translation might be – the place where

the people say Oc.

Rulership and in some

senses identity were tied to multiple origins – geographical, familial, and

political. The concept of the

nation-state is not generally considered to have emerged until the 15th

century at the earliest, and is generally considered to be a 18th

century European phenomenon.

During the Middle Ages states expanded, shrank, emerged,

and collapsed – borders shifted and disputed territory was conquered, annexed,

subjugated, or liberated in both diplomacy and war. However perhaps due to a general human desire

for narrative consistency we have a tendency to treat countries and their

predecessors as part of the continual progression with little distinction

between the two. The existence of such

distinctions is over passed over unremarked except where particular political

factors come into play. This was the

case during the campaigns leading up to the Referendum on Scottish Independence

in 2014 when there was some discussion over the position of the Queen – with

there being some suggestion that the situation would revert to that prior to

the Act of Union in 1707 which Queen Elizabeth II remaining head of state of

both the remainder of the United Kingdom and of the newly independent

Scotland. Of course, this reality did

not take place, and the potential shift has probably fallen out of the general

public consciousness.

Terminology can also shift. For example during the Cold War countries

were often divided into the First World (Western capitalist economies), the

Second World (Soviet style command economies), and the Third World (made up of

states which were not aligned to either the NATO or the Warsaw Pact). The term Third World became synonymous with

developing countries – sometimes referred to as the Global South. It must be noted that this model originated

in the capitalist West and has the ideological fingerprints of a Western,

NATO-centric, concept all over it. The

term Third World became particularly associated with former colonies of Western

states after they had either won their independence, or be granted it by the

states they had been subjugated by in the past.

The attitudes prevalent within a Western colonial mindset were equally

responsible for the split of the Third World with the least developed countries

sometimes pejoratively being referred to as the Fourth World. The concept of the Fourth world has existed

within extensions of the Three Worlds model previously – though not widely

accepted – since the 1970s to discuss the relationships between ancient,

tribal, and non-industrialised nations which are either marginal states or

stateless. It is sometimes summarised as

‘nations without states’ – and is often used in relation to First Nations in

the Americas, indigenous tribes in South America and some islands which fall

territorial within other states but have no links with them or communication,

and nomadic populations such as the Berbers (or Amazighs, which includes the Tuareg people for example) and the

Roma. These populations do not map to state

boundaries.

|

| The Berber Flag used since the 1970s, and formally adopted in 1998. |

|

| The Roma Flag adopted in 1971 (some variants exist) |

The short summary is that due to the fact that the

nation-state is a relatively recent concept, that it cannot encompass many

human populations, and the fluidity of national boundaries and identities using

broader geographic terms when establishing the boundaries of studies avoids

confusion around both political and cultural boundaries and identities. Once this is established, then locations and

areas can be mapped to both contemporary and modern locations in terms of

geopolitics in an easy to understand way.